Right and wrong and Robert Adams

On seeing the exhibition "American Silence" at the National Gallery

“Each of us welcomes quiet. As a private person, a citizen, and a photographer, these are some of the words I find myself remembering and repeating.” –Robert Adams

The exhibition opens with churches, near identical to each other, each standing alone on the emptiness of the plains.

Robert Adams has never been secretive of his faith—that he has faith—even though he prefers to let his art express it without further definitions.

He has published a small edition book titled Prayers in an American Church (Nazraeli Press, 2012), containing 12 quoted prayers and 17 photographs. Not all the prayers are Christian, or prayers. The photographs are of trees.

A pervasive element throughout Adams’s work is pure light and the sky. There is always an on-going dialogue: the inhuman landscape, our home; the human landscape, the home that we have built; the sky pouring light onto it all equally, or swallowing it all apart from our artificial lights at night.

These are of course elements in nearly all photography, but Adams’s minimalism ensures they engage in a subtle dynamic drama. The elements that would otherwise only be the necessary conditions for taking a photograph become actors on the stage of the film negative: space, objects and light.

The light lays its hands on everything alike: tract houses, strip malls, mountains, litter. In all of his work, only the churches in Adams’s earliest published book, White Churches of the Plains (1970), reach towards the sky. And the trees, trees everywhere.

Sometimes the sky in Adams frames is like a dream of the Creation, a space for timeless processes contained in their realm of purity, with the fractal human landscapes of new development sprawling below, somehow seeming to extend further than the boundless sky, an infinity of repetition and boundaries.

“Art does not deny that evil is real, but it places evil in a context that implies an affirmation; the structure of the picture, which is a metaphor for the structure of the Creation, suggests that evil is not final.” –Robert Adams

Adams is afraid of moralism even less than of open faith. He has made statements reminiscent of the grumbles of my Finnish grandfather about the sad state of modernity when jet skis blast by our row boat on an otherwise calm summer evening, or of the pessimism of another Finn, the fisherman of the apocalypse, Pentti Linkola.

There is a notion of nature as something good in itself, pure when beyond our touch, that we should respect and live in harmony with. Beyond the near-tautological truth of destroying the environment we depend on being wrong (which of course we do not respect), it’s a foundational assumption or derives from other foundational assumptions, such as faith (codified or loose and personal) or worldview. It’s an aesthetic but also a philosophical stance on life and the universe.

Hayao Miyazaki is often seen as a similar moralist of ecological bent, which is supported to some degree by isolated viewings of some of his most famous films. However, even in them there is no single party that is clearly evil, not even the exploiters of nature. They are simply attempting to thrive too.

Miyazaki’s Nausicaa manga, which extends much beyond the scope of the film, reveals the true complexity of his thought (which he has said he otherwise limits to suit the length of a movie): everything is the same process, the same physics, the same logic of evolution, of thermodynamics. The heroine gives up on her attempts to restore a putative “original state”, and accepts to live in the present, embracing the always-corruptness as part of the world and life.

Adams has taken photographs of fields of tree stumps, broken clear cut forests, giant stumps the size of a tiny house. Scarred quarries. Desertification. The style is simple, documentary, but the fury is there, the angry walker. The pristine forest gone. (He has photographed the pristine forest too, of course.)

These photographs are well executed, and serve as conduits of a healthy message of wrong and right, of ugliness and beauty, good and evil; they give us evidence against hope, as Adams himself has said, but elsewhere he always finds reasons for hope, and for him, hope prevails.

The photographs of Adams that speak to me most seem to forget about good and evil and to exist beyond this dichotomous struggle, and approach something that to me feels simply like truth.

When I look at the Adams photographs that are near ecological commentary, I don’t see something that allows me to feel superior in my state of moral condemnation, as an opposer of clear cuts, of being pro-nature, as if I gave a like on a political social media post and felt like the political duty of the day has been done, my position in the good team re-asserted once more, the evil kept on the outside.

Rather, an image of a clear cut is a reminder of our participation in a system that perpetuates such practices. It’s a mirror: one should imagine oneself enmeshed in the machinery that did it. Either accept it or fight it and renounce everything that relates to the practices one does not endorse. How many of us do that? What does it ultimately mean to be morally moved in an art gallery, or when browsing a photo book? Is it a reminder of hope, an impetus to do better? Assertion and embrace of faith in humanity? Or is it sentimentalism, the photo book one is holding printed on the same trees that were cut?

The photographs of Robert Adams that I find most interesting seem disaffected, even stilted. Fully ambiguous, a question posed, precise and haphazard at the same time, like the subject matter. Some of his photographs I could imagine raising the question in some viewers of, why is this a photograph? As good a sign of art as any.

The true harmony between us and nature. A bird on an electric line, the lines cutting across the image without beauty, and thus truthful and beautiful. Streaking the pristine sky like we do in planes. The cars on the road the most orderly presence, lined up. Trees localized chaos, with their inhuman arborization, subjugated but relentless. The cut field a momentary victory of order against entropy. The haze either morning mist or pollution; they’re both particles in the air. The elements strewn across the frame like things we see every day, messy, but framed with grace and intelligence. Why was this photograph taken? To show us the truth, how things simply are.

Forgiveness is impossible without compassion. Compassion is impossible without letting evil in, to perceive within the capacity for it. Is it then evil, if it also within? What is good, if one does not act according to what one believes is good? A picture may be black and white but be morally grey.

I’m particularly fond of the photographs Adams took in interior spaces, supermarkets and especially homes. His minimalist aesthetic transferred to such spaces becomes near comical, even self-aware, ironic, but somehow, still invites something like the sublime and the impartial with the purity of the frame.

There are indications that his notion of evil is not one of misanthropy, despite it sometimes perhaps appearing that way. Evil is rather something impartial, the rite of the everyday, commerce and its consequences, the oblivion of denial and inattention, lack of consideration for the consequences of one’s actions, unwillingness of imagination and empathy; the necessities of everyday life.

He risks such compassion, fights the tendencies of the lone walker and observer, walks up to people and faces them, or at least lets the lens of his camera and by extension him face them in the solitude of his darkroom, and then us face each other and ourselves when viewing and contemplating his work.

His compassion for his compatriots is most evident in his series on families at the parking lots of various strip malls. His anxiety of facing people, taking candid photos, the guilt and shame, the fear, the courage of engaging despite this, is sometimes concretely visible in the photos as shake. He would hold the camera strapped to his wrist, hide it behind a plastic shopping bag, release the shutter, in almost a form of prayer for his subjects; not using them, noticing them, roll after roll, excavating the serendipitous frames of grace in the darkroom at his home.

Like most walker photographers, Adams is often interested in facades. In his later work, he has invited his audience behind his, offering to share the small joys of home and yard. There are several such volumes. It relates to the restrictions and limitations of old age, but also shines light on the sanctuary of privacy, the duty to make one’s home a place of hope, welcoming, yet separate, offering protection of the spirit, room for creativity to take flight, like the models for his wooden bird carvings.

One of my favorite titles of his, for its simplicity and earnestness, is I Hear the Leaves and Love the Light, a somewhat neglected book of photographs, exclusively taken in his backyard, of his dog enjoying both leaves and light.

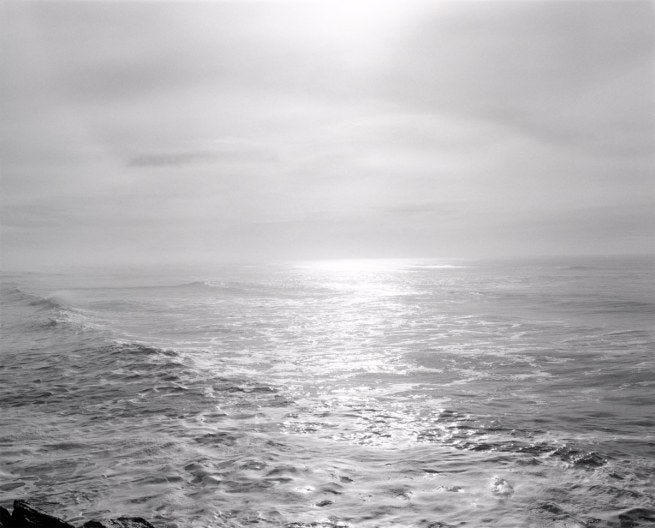

The last work of Adams to have featured in the exhibition at the National Gallery (which exhibition I realize I’ve gone beyond in this survey; I don’t think the dog photos made it, unfortunately) finally finds him at the last frontier of life, face to face with the sky dissolving in the horizon with the ocean, walking on the shores of the Pacific, close to his home in the Northwest. It’s still a celebration of life—people, driftwood, birds dot the landscape—but it is also an artist coming to terms with and embracing the beyond, near the inevitable end of his life. A perhaps final act of photographic courage, to last hopefully for several years to come, each photograph evoking the rolling of the waves, the rhythmic drone that nearly always brings one to the present moment, reminding us to be grateful.

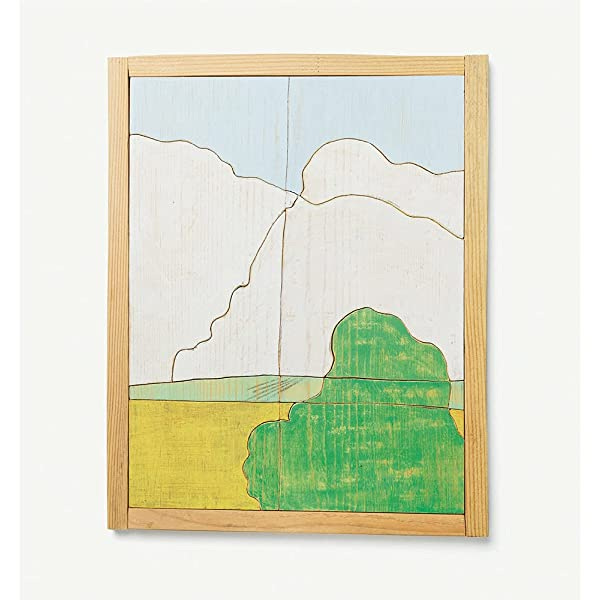

Interestingly, considerations of death and eternity are not the final output of Robert Adams or his last statement. He’s picked up pieces of driftwood from the shores on his walks of contemplation, brought it home, carved the mentioned birds out of them, but also started to use them as canvases, spurred on by recollections of his prior walks in the plains reflected in the patterns of lines and fractures in the wood. Another affirmation of life.

Yes, photographs are only convincing if the photographer pays attention to the facts of life, but photographs have to point beyond the facts. –Robert Adams